International teams are supported by very similar pillars as national teams but these have to be looked at from an intercultural perspective. By doing so, it is possible to identify different approaches and commonalities for highly effective teamwork.

1. Common goal and understanding

International teams need clear and comprehensible goals with which all team members can identify.

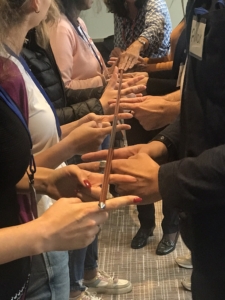

Even if the goals are usually set externally, it is necessary that each team member has the opportunity to communicate his or her interpretation of the team goal, so that a common vision can be developed within the team. To ensure a good start to the project, a positive attitude and a common focus on the task at hand is needed; international teams in particular must allow sufficient time for this.

At first, some team members may feel as if they are being looped unnecessarily, when at the end of the meeting the same goal formulation is repeated as at the beginning: “We’ve been here before!”. Being aware the many circles, perspectives, discussions around this formulation is absolutely necessary in order to find a consensus at the end and to look together in one direction; among other things also because the same words (e.g. ‘friend’, ‘concept’, or ‘tomorrow’…) have a different meaning in different languages, and cultural contexts which can lead to misunderstanding.

2. Coordinate processes and communication

As in national teams, processes must be coordinated in international teams. However, this becomes even more important from the perspective of an international team, as culturally influenced ways of working often collide here.

Sometimes, for example, different cultures have a different understanding of hierarchy (different power distance):

What roles are assigned in the international team and what responsibilities do these roles have?

What does our decision-making process look like?

Even more examples can be found in time management:

What does “on time” mean to us?

How quickly do we usually receive feedback?

Problem-solving techniques, rules and tools:

Do these apply universally and are they binding for everyone, or are deviations permitted in individual cases?

There are also culturally different degrees of uncertainty avoidance:

What does our risk management look like?

Communication habits:

How clear and explicit do we need information to be?

Is a meeting kept short and are only the most important topics discussed or are very detailed plans made?

Here is a quote from A. Stang, a German employee of a German company based in Ireland:

“In our teamwork in the German-Irish team in Dublin, we tried to implement this synergy building in our weekly team and work meetings, which was not always easy – especially because our German team sometimes brought the Irish team members to the brink of despair due to their “passion for deep analysis”! So we agreed that we would continue to have regular team meetings, but limit ourselves to the essential things (as usual in the Irish context) without going into detail every time and limit the meetings to max. 1 hour weekly.”

Sometimes, it is not necessary to agree on a common standard. It can be advantageous to focus on the achievement of the goal instead of on the question: How do we reach the goal? The team leader and the team must agree and commit on what to focus on. Overall, it is precisely here that the “holy search” for creating synergy and developing an individual team culture must begin.

3. Mutual trust

When there is a lack of trust in a team, chaos is inevitable: Information is withheld, everyone tries to protect themselves, small misunderstandings escalate into serious conflicts, open communication is a foreign word.

Different cultures have different concepts of trust. In addition to different personal views about trust we are influenced by our cultural background. In some cultures for example, people will tend to give strangers ten plus points on the trust scale at the beginning, which can be reduced by bad experiences. In other cultures, people will be more distrustful at first and will tend to give ten minus points at the beginning, which can be reduced by good experiences. The topic of “trust” should therefore not be regarded as a by-product, but should be explicitly put up for discussion:

- What does trust mean to us?

- What criteria do we associate with trust?

- How can each individual team member tell that he or she can trust the others?

- What can we actively do to develop or build mutual trust in the team?

This topic is particularly important for virtual teams, which have fewer opportunities to build trust in face-to-face contacts.

Research shows that, when team members have built intercultural competence, multicultural teams are much more performing and innovative than monocultural teams.

This is one of the great chances of our global economy and intercultural team development is a key lever to unleash this potential.